Most dictionaries define “war of nerves” as the use of psychological means to undermine or wear down an opponent’s resistance. They trace its origin to World War II. But the origin actually goes back to World War I, and its use and meaning went through subtle changes through both wars and beyond.

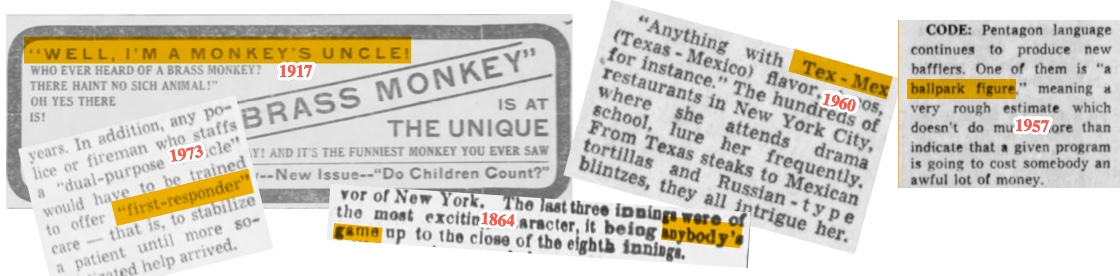

(NOTE: My research on this term began as part of my work helping author Paul Dickson find earliest uses of terms for a planned World War II dictionary. I’m also working with Paul on finding earliest uses of baseball terms for a possible new edition of his The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, first published in 1989 with updates in 1999 and 2009. For more on the baseball efforts, see my First Up website: https://baseballterms.kenliss.com)

World War I

The earliest use of “war of nerves” that I could find was in an article by Charles Tower in the London Daily News on November 24, 1914.

Reporting on an interview with General Paul von Hindenburg in the German-language Swiss newspaper Neue Freie Presse, the article cites Hindenburg, in translation, as saying:

“The war with Russia at present is principally a war of nerves. A General Staff must have no nerves, for a nervous General Staff infects the whole army with an uneasy spirit. If Germany and Austria-Hungary have the steadier nerves, and will hold on, they will win. And they will have the better nerves, and they will hold on.

Paul Von Hindenburg, in Charles Tower. “The German View. Von Hindenburg on His Russian Foe.” London Daily News, November 24, 1914, p3

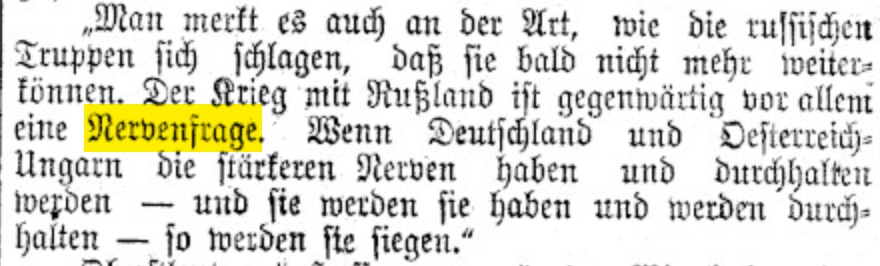

Neue Freie Presse is available online, and I was able to find the original article. (November 19, 1914, p2). Hindenburg actually uses the word Nervenfrage, meaning “question of nerves,” not Nervenkrieg (“war of nerves”), so credit for the phrase goes to whoever translated the article for the London paper.

The term then appeared in both British and American newspapers several times over the next few months. For example:

The Dublin Daily Express noted a German newspaper remarking on the fighting quality of French and British soldiers, with the Express commenting that: “No better augury could be offered for the certainty of such an army’s ultimate triumph – particularly in a ‘war of nerves.’” (“Air and Sea Warfare.” Dublin Daily Express, December 28, 1914, p4)

The Times of London in March 1915 reported on an article in the Turkish newspaper Tanin with the headline “A ‘War of Nerves’” about the bombardment of the Dardanelles. The Times article notes that the Turkish paper borrowed the heading from Hindenburg’s expression. (“A ‘War of Nerves’”. The Times, March 3, 1915, p29)

An article in Collier’s by American war correspondent Frederick Palmer had the following passage that perhaps best explains why this new kind of warfare was a “war of nerves”. (I don’t have the date of the Collier’s article but it was quoted in several American newspapers in April 1915.)

In the old times you fought for a few hours and the battle was over. If you were uncertain of your courage you took a drink before you charged. Now you fight day after day; you face the enemy in apprehension that at any moment a shell may bury you alive or eviscerate you. Hand grenades are tossed back and forth like bouquets. It’s a war of nerves, and in this age of nerves the highly civilized man is standing what would utterly demoralize a savage.”

Frederick Palmer in Collier’s, quoted in “Twentieth Century Courage.” Daily Nonpareil (Council Bluffs, IA), April 23, 1915, p4

There was even this odd commentary about the importance of keeping Indian tea out of the hands of the Germans:

“It has been authoritatively pointed out that this is a war of nerves and tea is a powerful steadier of the nerves. In so evenly contested a struggle as the present everything counts. By just so much as Indian tea is better than other tea will be [sic] German soldier be a better man by the use of it and many a British soldier will be slain by the added accuracy of German fire due to Indian tea.

“Calcutta Tea Trade.” Englishman’s Overland Mail, February 14, 1915, p18

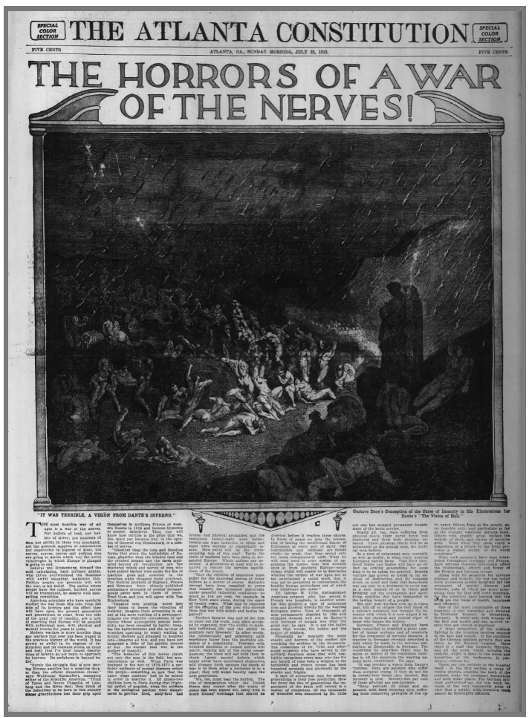

Perhaps the best example from World War I is this cover story and opening passage from the Atlanta Constitution on July 25, 1915:

The most horrible war of all ages is a war of the nerves. Not bullets of lead, nor bullets of silver; not numbers of men nor ability of those in command; not the greatest supplies of ammunition nor superiority in bigness of guns, but nerves, nerves, nerves and nothing else are going to decide which way the awful catastrophe in which Europe is plunged is going to end.

General von Hindenburg, himself the cold, calculating, hard military genius, who thrice overwhelmed the Russians with awful slaughter maintains this. Neither armies nor generals will win the war, is his belief. The nation whose people have the calmest, hardest nerves will be triumphant, he asserts with compelling conviction.

The Lead-Up to World War II

The term “war of nerves” began to appear in British newspapers again in April 1939. This time it referred to Hitler’s attempts at intimidation. As in 1914, this use of the term seems to have begun with the Germans, as indicated in the following early examples:

German broadcasters have been boasting that their country has won ‘the war of nerves.’ They assert, rather anxiously that this is proved by our work to make ourselves prepared. But it is no sign of nerves to take one’s hands out of one’s pockets when a bully approaches. We have done no more than that. But our hands are out of our pockets. If we are anxious, it is not because we are afraid of defeat.

“Anxiety or Nerves.” Western Gazette (reprinted from Daily Sketch), April 21, 1939, p16

The forces against aggression are in a far better position to resist pressure than was the case last autumn. They have no need this time to fear the prolonged ‘war of nerves’ unmistakably threatened by some inspired German scribes.

J.L. Garvin, “Peace or War.” The Observer, April 23, 1939, p14

It can be safely said even that the general public is, in certain respects, ahead of the government, in so far as their intentions are at present known, in its appreciation of the steps which are called for in this country. On the other hand, the Ambassador should also be able to indicate in Berlin that what the ‘Angriff’ [Der Angriff, a Nazi party newspaper] has called a ‘war of nerves’ cannot successfully be prosecuted at the expense of the British people.

“Sir Neville Henderson’s Return.” Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, April 25, 1939, p8

We have been threatened with ‘a war of nerves.’ It would be truer to say that that war has been in progress for some time. I do not know whether we are winning or losing because I have not had any chance lately of observing the other side, and in this matter I would trust nothing but my own direct observation.

J.B. Priestly. “How to Live in 1939.” London Daily News, May 1, 1939, p10

The term came to be used increasingly to refer to German pressure on Poland, in both British and American newspapers.

The choice facing the Fuehrer, Pertinax [Andre Geraud] said, is between straight military force and a combination of diplomacy and propaganda, which won him Austria and Czecho-Slovakia. If Hitler chooses force, Pertinax said, that obviously means a world war. If he chooses the other tactics it means a war of nerves which may last all summer.

Edmond Taylor. “Hitler’s Threat to Chase Poles to Siberia Bared.” Chicago Tribune, April 30, 1939, p3

His Government is anxious not only for first-hand information on the Anglo-Russian talks, but also to inform him of the full facts, and the Polish Government’s full views, on the Danzig incidents. It is feared that there may be a sequence of planned incidents with a view to working on Poland’s nerves and either weakening her resistance or provoking her into some rash action.

The War of Nerves.” Liverpool Daily Post, May 23, 1939, p8

In World War II

Once the war started, the term took on a broader meaning in the English language press, encompassing the nerves of soldiers, government leaders, and, increasingly, the civilian populations of the warring countries.

This use of the term was foreseen even before the fighting began. In May 1939, the Scotsman newspaper interviewed Sir John Anderson, the Lord Privy Seal:

’In a future war,’ added Sir John, ‘it will be vitally important to keep up the heart of our people. The war of the future will be not merely one of men and machines; it will be a war of wills and a war of nerves. It will be the nation with the strongest will and the steadiest nerve that will come out victorious in the end.’

“Sir John Anderson’s Appeal.” The Scotsman, May 11, 1939, p6

A few days into the war, the Coventry Herald carried these lines:

The war of nerves that has been going on for so long has become a war in reality, in which more or less all are engaged, soldiers and citizens, and the only way to meet and successfully overcome what lies before us is to set our teeth with grim determination to see it through until victory crowns our cause.

“Coventry is Prepared.” Coventry Herald, September 9, 1939, p4

After the fall of France and beginning of German bombing raids on England, the war on the nerves of the British population became more concrete.

War in the Air. Thirty years ago that was the title of a book, and a piece of prophetic fiction. Since then it has become grim reality. And now that Wellsian dram has come true in the South-West, where last night three lives were lost. Bombing raids have two aims: military objectives and the morale of the civilian population. In pursuing the second purpose the enemy bomber wages a war on nerves.

“War in the Air: Facing Up to Hitler’s Nerve Test.” Express and Echo, June 25, 1940, p3

Berlin’s ‘war of nerves’ against England is now entering is second and more vital phase with a rapid increase in bombing by day. The Germans have found that day bombing on a wide-awake people in their shops and businesses has a much more devastating effect that night attacks which have only at most an atmosphere of unreality. In London the impact of nervenkrieg is being felt more strongly.

Frederic Sondern, Jr. “The European Whirligig.” Sunday American-Statesman Austin, TX), July 7, 1940, Section 2, p6. [Syndicated column also appeared in other papers on the same date. This is the earliest use of the German word Nervenkrieg – “war of nerves” – that I’ve found in an English language paper. That would seem to indicate that it was being used in the German press.]

Fear of a Nazi invasion also played on the nerves of the British public:

A high official at the German Air Ministry is quoted in a Berlin dispatch to the ‘National Zeitung’ [German-language newspaper in Basel, Switzerland] for the statement that the invasion of Britain would certainly come … Commenting on the official’s statement, the paper asks what was the purpose. It suggests that it might be in order to hide the Germans’ real intentions or to wear down the enemy’s nerves, making him readier to compromise, probably also to stimulate Germany’s own morale.

Invasion Threat: Real or War on Nerves?” Belfast News-Letter October 1, 1940, p8

Bombing and, in 1944, the threat of invasion, also worked as a “war of nerves” against Nazi Germany.

We have ascertained in three days only that no part of Germany is inviolate from Polish or British airmen, and we can be sure that the German populace has taken notice of the fact. Germany wanted a “war of nerves’ so it is only fair that she should share in it.

“The Fourth Day.” Newcastle Evening Chronicle, September 6, 1939, p4

Our advantage lies in the enemy’s ignorance of where we shall try to land. It is the best kept secret in the history of armies, and holds the German forces dispersed over hundreds of miles of coast. For them the war of nerves has begun, and the period of waiting will increase the strain.

“German Ignorance of Invasion Plans.” “Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, January 4, 1944, p1

The term was also in the Pacific War, although later and to a lesser extent.

Non-Military & Later Uses

It didn’t take long, after the revival of the term “war of nerves” in the spring of 1939 for it to be used in a non-military sense. Not surprisingly, given the common use of military metaphors in sports, it soon appeared in sports stories in both the U.K. and the U.S.

“… Lancashire and Yorkshire matches, which have become in recent years ‘a war of nerves’ have an appeal that is all their own; and even though they have so often ended in disappointment for Lancashire, they remain the most thrilling features of the country’s cricket season.

“Sporting Occasions.” Liverpool Daily Post, May 27, 1939, p8

This National league pennant fight has become a ‘war of nerves,’ with the baseball world waiting to see whether the Cincinnati Reds or the St. Louis Cardinals crack first.

Judson Bailey, AP. “’War of Nerves’ in National Loop.” Globe-Gazette (Mason City, IA), September 23, 1939, p9

It is a war of nerves which is now being waged between Rose Bowl teams, preparatory to the outbreak of open warfare Jan. 1.

Wirt Gammon. “Rose Bowl’s War of Nerves.” Chattanooga Daily Times, December 21, 1939, p15

Joe Medwick, slugging outfielder, voluntarily signed his 1940 contract with the St. Louis Cardinals tonight, ending a long and stubborn holdout siege. Ending the war of nerves between himself and the club, Medwick reportedly signed at the Cardinals’ terms for $18,000.

Associated Press. “Joe Medwick Signs—And on Cards’ Terms.” Chicago Tribune, March 27, 1940, p21

The term was also used during the war to describe labor disputes in both Canada and the U.S.

’The strike has developed into a war of nerves between the Quebec Municipal Commission and the strikers,’ one of the committee members announced following yesterday afternoon’s session.

“City Workers Told Make Strike Total.” Montreal Gazette, January 4, 1944, p9

John L. Lewis subjected the Nation to a growing ‘war of nerves’ today over whether his United Mine Workers will call a soft coal strike on March 31.

United Press. “Lewis Waging ‘War of Nerves’ in Coal Parley.” Evening News (Harrisburg, PA), March 7, 1945, p9. [Widely syndicated]

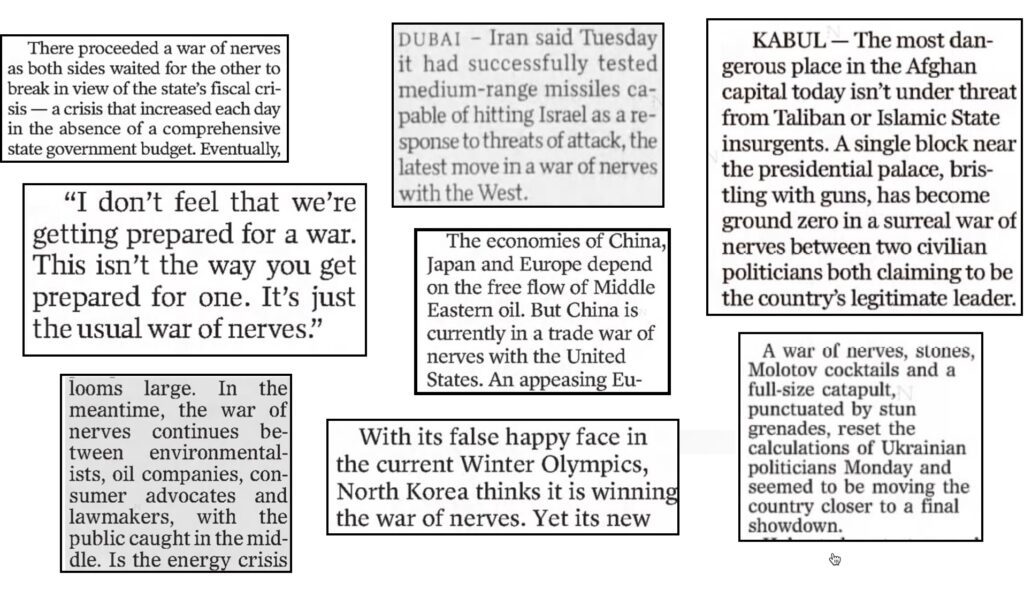

The term continues to be used today, in both military, quasi-military, and non-military ways, more than a century after it was first used in World War I.