Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

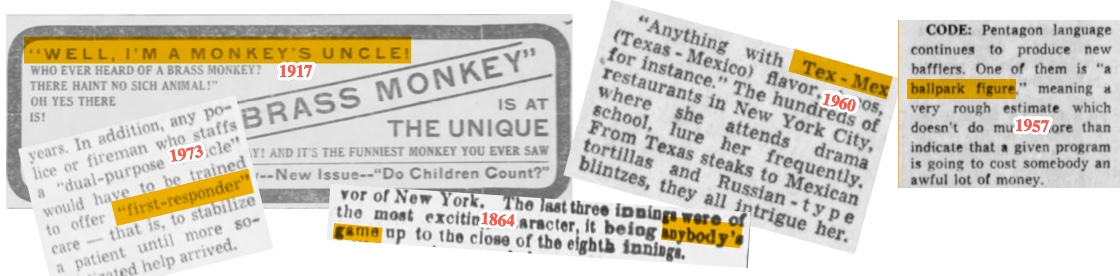

This post is not about the etymology of four-letter words, but about the term four-letter word as used to mean an obscene or offensive word. The term was used that way in newspapers in both the U.S. and the U.K. as early as 1886. But — not surprisingly — the words the term has been applied to have changed.

For many years, hell and damn were the words most commonly referred to in print as four-letter words (with or without the words themselves being printed). Words we associate with the term today do not seem to have been referred to even obliquely in the press. (They were, of course, around long before 1886; just not in the press.)

As late as 1921, Charles G. Dawes, a future vice president of the United States and Nobel Peace Prize winner, caused quite a stir using hell and damn at a Congressional hearing. His words were widely reported in the press, but were expurgated in the official transcripts of those hearings published by the Government Printing Office.

Even the word liar was once referred to as a four-letter word, something dignified people would never utter publicly to describe another person. Teddy Roosevelt had a lot to do with changing that.

The Dawes and Roosevelt examples are odd stories worth telling, and I’ll have more on both of them and their four-letter words. But, first, let’s look at the earliest uses of the term.

A Place in [a Four-Letter Word]

The first example I’ve found comes from the Davenport News in Davenport, Iowa, in April 1886. A correspondent named D.N. Richardson, writing from Bombay (now Mumbai) in India, describes a facility where old, lame, and injured animals of many kinds — cows, sheep, cats, dogs, ducks, and chickens — are cared for and provided for.

Who has done this? Well, he was a heathen! And he is dead! You can tell in a four-letter word right where he is putting in his time….”

Davenport News, April 10, 1886, p1 (Also appeared in other papers)

That may sound like criticism. But, in fact, the correspondent, although he may have expected the non-Christian “heathen” to be condemned to spend eternity in hell, was actually praising the deceased man for leaving money for such an effort, in contrast to the way Western societies treated aged and infirm animals and even humans.

In May of the same year, a letter to the editor of the Irvine and Fullarton Times in Scotland referred to

….that–to some–obnoxious fowre-letter word, ‘hell,’….”

“Dear Maister Editur,” Irvine and Fullarton Times, May 14, 1886, p3

Here’s another early example of four-letter word used to refer to hell:

[A]s theology has become weak, and prances on doddering and discordant legs, on account of the ignorance of the doctrines contained in a four-letter word beginning with ‘h’; so society pulls apart and not together….”

“A Paradise of Brides,” New Haven Journal and Courier, November 8, 1895, p7

Damn, Darn, and “A Tinker’s Malediction”

The word damn (and derivatives like damned and damnation), appeared often in the press, but this word, too, came to be referred to as a four-letter word.

An 1894 article in the Kapunda Herald in Australia about a dispute over the sale of land, quoted one proprietor as complaining about the low value placed on some South Australia land:

‘[I]f Alanby land is land is worth only £2 an acre, land in many other parts of the colony will not be considered as worth ‘a tinker’s malediction.’ Only [continued the reporter] he used a four-letter word instead of ‘tinker’s malediction.'”

“Scratchings in the City.” Kapunda Herald, June 8, 1894, p3

The phrase tinker’s malediction was itself a delightful euphemism for tinker’s damn. See this excellent explanation/exploration of tinker’s damn from Patricia T. O’Conner and Stewart Kellerman’s Grammarphobia blog.

Even the more common euphemism darn was referred to as a four-letter word. An 1899 column in the Rockford (Illinois) Register-Gazette chastised young women for their use of “slang expressions” and “startling expletives” that are “positively vulgar.”

If you should be entertaining a young man friend, and he should so far forget his manliness to swear even the one little four-letter word which you are even afraid to utter, you would be indignant, and properly so. His invitations to your house would end. What do you do? What did I hear you say? ‘Oh! Darn it! I don’t care!’ Is that ladylike? Is it any better for you to use a word of four letters than for you to use a similar word–and in exactly the same manner too[?]”

“To the Young People.” Rockford Register-Gazette, September 23, 1899, p3

“Hell and Maria Dawes”

Despite being considered four-letter words, hell and damn continued to appear frequently in newspapers. One realm where they were rarely heard, at least in public, was politics. That’s what made Charles G. Dawes’ testimony at a Congressional hearing on war expenditures so noteworthy.

Dawes, a Chicago-based banker and businessman, had served as Comptroller of the Currency under President William McKinley from 1898 to 1901 and had unsuccessfully sought a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1902. He served in the military after the U.S. entry into World War I, rising to brigadier general and overseeing purchasing for the American Expeditionary Forces under AEF commander General John Pershing.

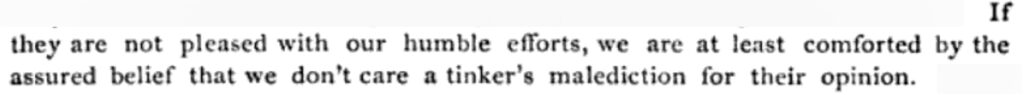

In February 1921, Dawes gave several hours of testimony before the House of Representatives Select Committee on Expenditures in the War Department. Seeking to dispel an impression of waste and inefficiency in military spending during the war, Dawes peppered his responses to questions with words not usually heard in the halls of Congress.

The Washington Star noted that Dawes had said there are two effective ways to get public attention: to weep or to swear:

Gen. Dawes used what is popularly but perhaps improperly styled profanity. He sprinkled his testimony with a few effective four-letter words that gave it what the general reader of news regards as ‘pep.’ These little words are in common use among men. They mean really nothing. They are mere accents. They are taboo in some circles. Precisians regard them as superfluous and some sternly religious people regard them as profane. But whether profane or inelegant these compact stresses put the testimony before the public vividly.”

“Putting ‘Pep’ Into the Hearing.” Washington Star, February 5, 1921, p4

Newspapers around the country reported how Dawes railed against members of the committee and others besmirching the reputation of the army and of General Pershing. He decried as a “hell-fire shame” the “damn critics” and “pinhead politicians who are raising hell” and “trying to make a mountain out of a damn little mole hill.” “You haven’t a damn chance to make out a case,” he told them.

“Hell and Maria!, he said. “We were fighting a war!” (It was his most quoted line –sometimes written as “Hell and Mariah” — and earned him the nickname “Hell and Maria Dawes.”)

The February 5th article in the Washington Star went on to explain the psychology behind Dawes’ use of such terms:

The spectacle of a man of eminent position sitting before a solemn investigating committee, with a stenographer present, and using language that while colloquial in many circles is not usual in testimony, impressed the public as an evidence of intense sincerity. Gen. Dawes said during one of the recesses that he realized that if he was not using the little words of a peculiar kind he would probably not get a ‘stickful’ in the reports. As it was he became a first page ‘story.’ And it was all because of those combinations of four letters.”

It was reported right away that Dawes use of these words would not be included in the official transcript in the Congressional Record. (According to one report it was decided even before the actual testimony.) You can read the transcript, minus the four-letter words, and compare it to what was reported in the papers.

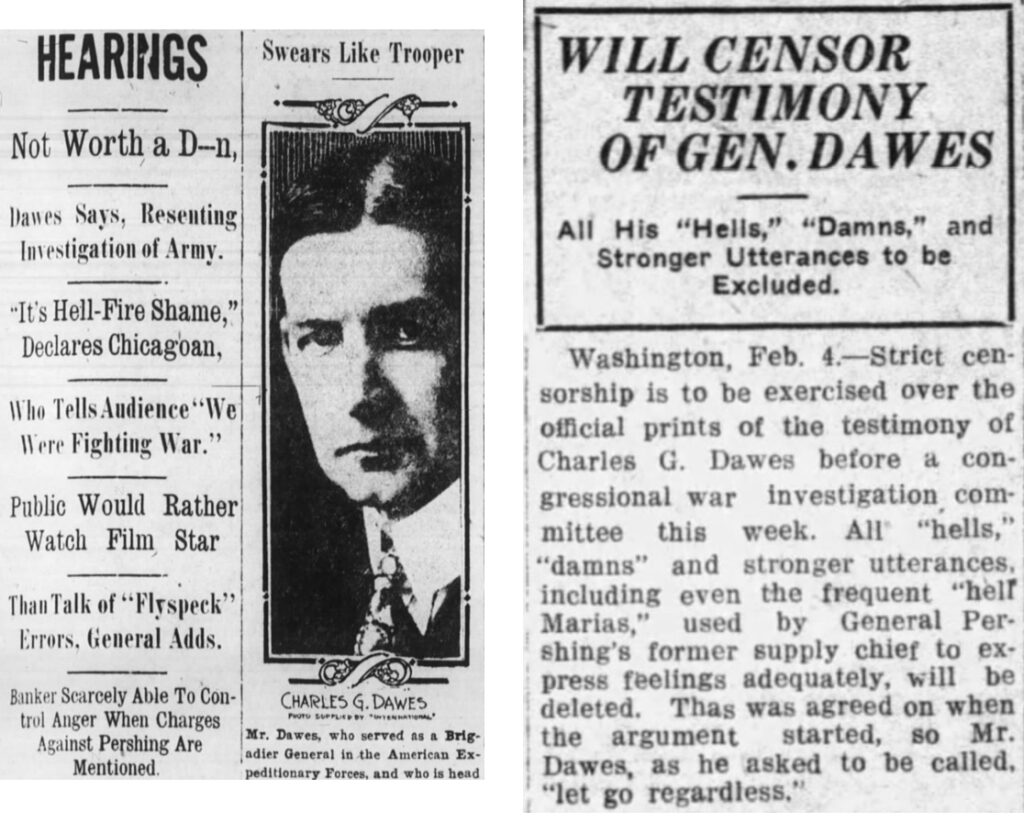

But that doesn’t mean they were forgotten. It was brought up again three years later when Dawes was nominated as Calvin Coolidge’s running mate in the 1924 presidential election. Opponents — one newspaper called him “Cusser Dawes” — said it made him unfit for office; supporters saw it as a sign of toughness and forthrightness.

Teddy Roosevelt and His Liars Club

The response to Charles Dawes’ use of hell and damn in Congress a century ago seems almost laughable today; see this 2019 article in The Hill about how much present-day lawmakers curse. How, then, should we think about the use of four-letter word almost a decade earlier to refer to the word liar?

A November 7, 1912 article — it appeared two days after Theodore Roosevelt lost his comeback bid for the presidency to Woodrow Wilson but had nothing to do with the election — described sports reporters who exaggerated accounts of college football games as

such ‘bare-faced’–followed by a four-letter word made famous by T.R.”

“Gridiron Gossip” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, November 7, 1912, p12

So how, exactly, did Roosevelt make the word liar famous?

As president, Roosevelt had closer relations with the press than was typical before his time. According to the Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University in North Dakota, “In the days before regular press conferences and formal press briefings, it was probably Roosevelt who began the tradition of meeting with reporters or groups of reporters, sharing background information, and answering many questions.”

But Roosevelt, according to the Center, bristled at criticism from many in the press:

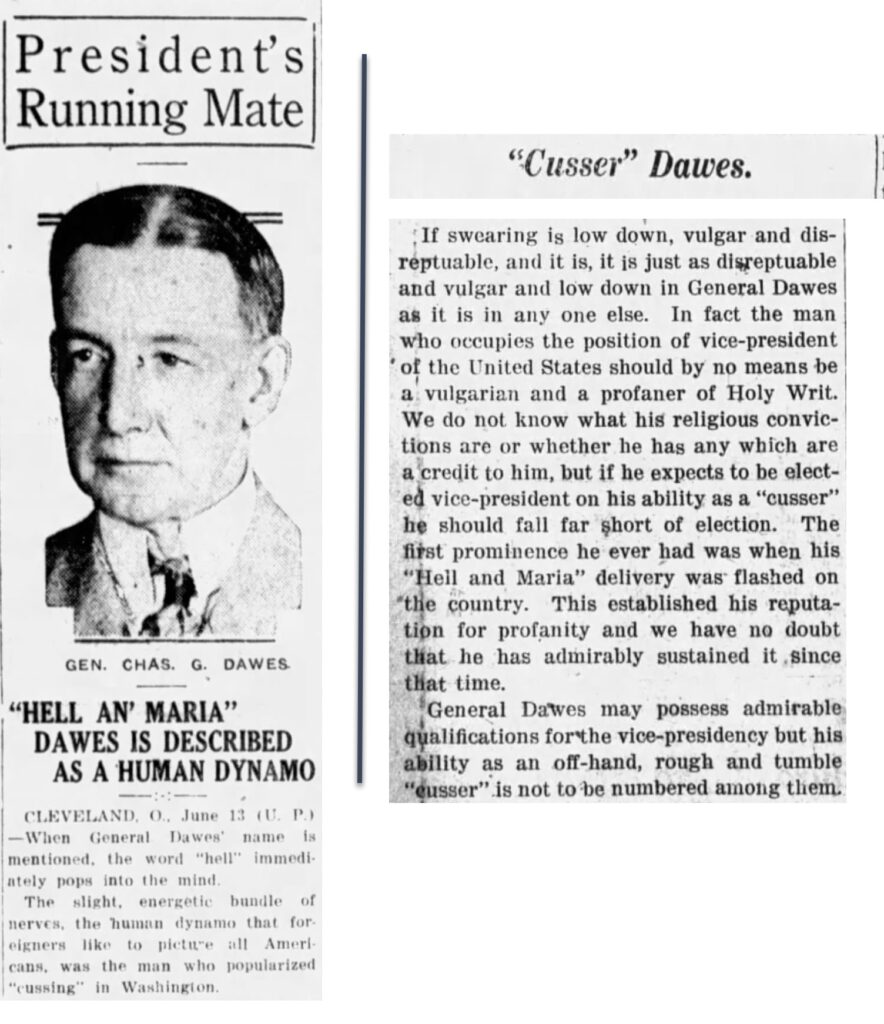

By the end of his term …. Roosevelt was known for calling a spade a spade, or a liar (in his view) a liar, which he did frequently. He invented an ‘Ananias Club’ for liars, after the New Testament figure who was struck dead by the Holy Spirit for lying to the Church Fathers about tithe offerings.”

Christmas cards!. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

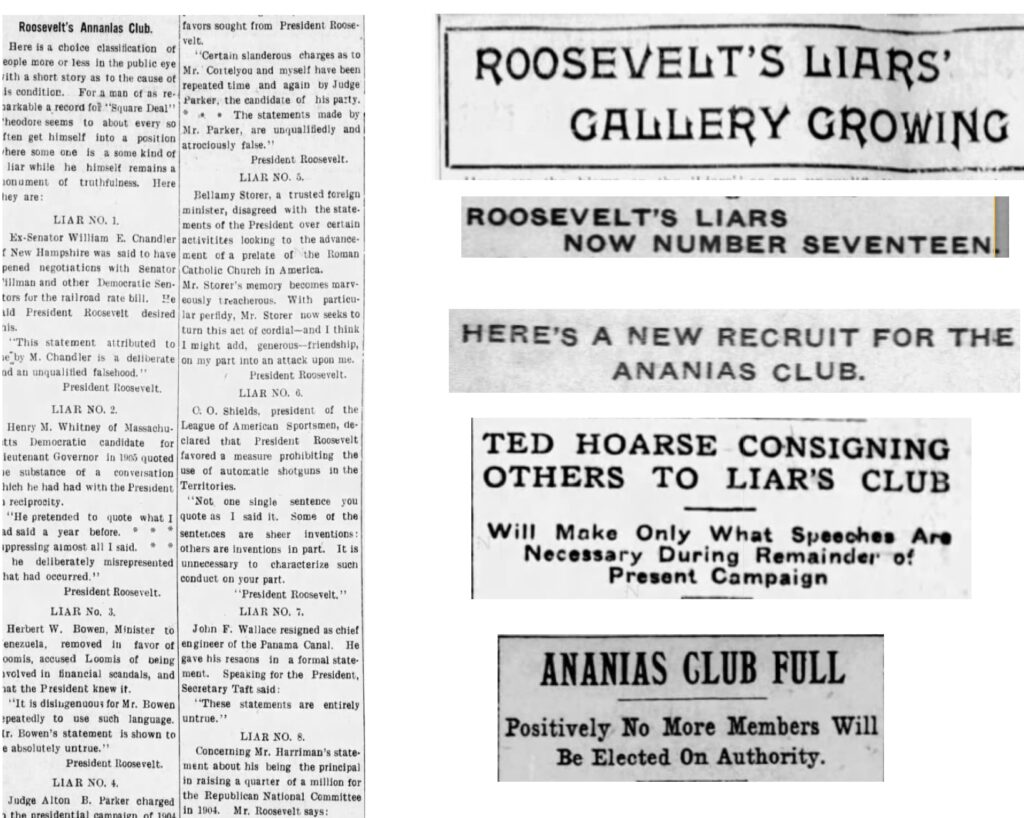

Irreverent “Ananias Clubs,” many formed by members of the press to target mendacious politicians, had existed for at least 20 years before Roosevelt started his own. But the use of the term coming out of the White House, targeting editors and publishers as well as other politicians, brought greater attention and many comments and editorial cartoons. (See more cartoons on the website of the Roosevelt Center.)

Newspapers tracked the growing numbers of members of Roosevelt’s liars club, both during his presidency and when he ran again on the Progressive ticket in 1912.

Not surprisingly, Roosevelt’s opponents were more than willing to turn the tables on him. For example:

Mr. Roosevelt’s Ananias Club is a peculiar one: in fact, it is different from any ever before formed in that its organizer does not care to be considered a prominent member of the same whether entitled to such position or not.”

Wilmington (NC) Messenger, December 13, 1906, p2 (Also appeared in other papers)

The former president’s liars club was remembered in newspaper articles after his death in 1919, perhaps none more fittingly than this reflection in the Salt Lake City paper Goodwin’s Weekly that glossed over the word liar itself:

If an enemy dared to criticize he was instantly denounced as a follower of Ananias. Roosevelt rang the changes on the ‘shorter and uglier word’ with a fertility of invention which no statesman has equalled. He was constantly seeking a new and pertinent way to describe some new adversary as a falsifier.”

F.P. Gallagher. “The Roosevelt Enigma.” Goodwin’s Weekly, January 11, 1919, p5

When Is a Four-Letter Word Not a Four-Letter Word

This post began with a look at how the term four-letter word, in the sense described here, was for many years used in print mostly to refer to the words hell and damn before moving onto other words. While many of those English language words are, indeed, four letters long, the term is sometimes used to refer to offensive words of other lengths.

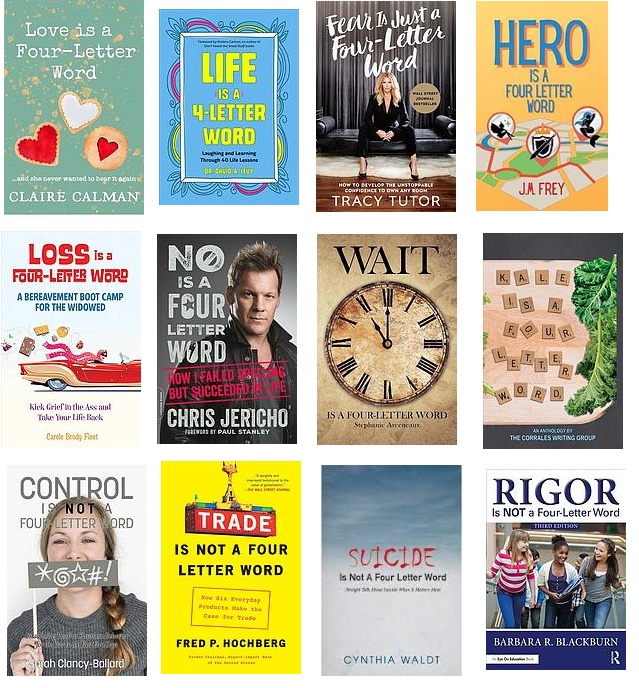

The term has also been applied, in the positive and the negative, to many non-offensive words (of different lengths) to make a point of some kind. Look, for example, at this varied group of book titles, all published in the last five years. (There are many more from these and earlier years.)

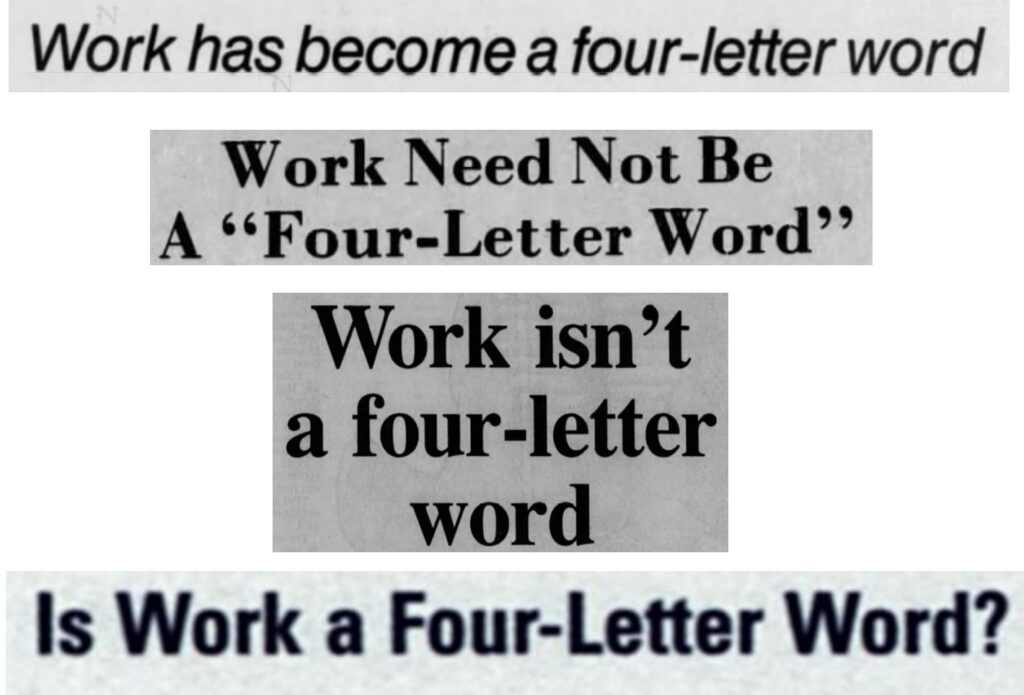

Then there is the word work, which has, perhaps, been given the four-letter word treatment more than any other word (other than the usual suspects). But is it or isn’t it a four-letter word? It depends on who you ask.

It seems fitting to end this language exploration with one more example, the title of a December 1993 article by a Florida middle school teacher in The English Journal, a publication of the National Council of Teachers of English.

Interesting post!