The term herky-jerky, which has been around since at least 1889, has been widely used in the last two years to describe the uneven, uncertain nature of life amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

It’s been used to describe public health responses, economic relief efforts, hybrid education plans, industry impacts, disruptions to sports and entertainment, and, as one news article put it, “herky jerky approximations of what used to be routine joy.”

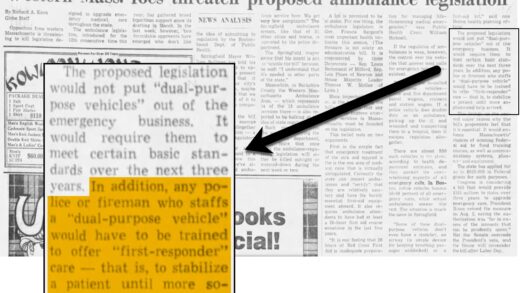

Even before the pandemic, the term, once used almost exclusively to describe the motion of certain baseball pitchers, had become more broadly applied. This year alone, for example, herky-jerky has been used to describe such non-pandemic-related topics as:

- the bobbing of pigeons’ heads

- changes in government policy on protecting grizzly bears

- the quality of a video of the police shooting of a black motorist

- the way traffic merges on a highway

- the elevator ride to the top of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis

- the 101 Dalmatians movie script

- the jagged guitar riffs of a rock band

- Elon Musk’s delivery on Saturday Night Live

- and much more

But when and where did this term originate?

Origins and Changing Meanings

The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, where I began my exploration of this term, defines herky-jerky this way: “Said of the motion of a pitcher with an esp. awkward delivery.”

But general dictionaries offer broader definitions:

“Characterized by abrupt stops and starts, or jerking movements.” (OED)

“Characterized by sudden, irregular, or unpredictable movement or style” (Merriam-Webster)

“Having an irregular spasmodic movement. ” (Wiktionary)

Which came first?

The Baseball Dictionary doesn’t give a first use of the term, but the earliest citation in OED, from 1890, appears, at first, to fit the sense of a baseball pitcher’s delivery.

![1890 Oakland (Calif.) Daily Evening Tribune 3 June 7/1 John Levy, with..a herky-jerky deliv[er]y, said he was bridgetender on the Webster-street bridge.](https://etymology.kenliss.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/herky-jerky-bridgetender-1024x135.jpg)

But, in fact, the “delivery” used in the article refers not to pitching, but to speech (like in the 2021 description of Elon Musk’s delivery on SNL). Here’s the full 1890 citation, describing a witness at a hearing on an accident in which 13 people were killed when a train went through a warning signal and plunged into a creek:

John Levy, with a fine Hibernian accent and a herky-jerky delivery, said he was bridgetender on the Webster-street bridge in the employ of the railroad company.”

“Dunn Gone: The Engineer Not at the Inquest.” Oakland tribune, June 3, 1890, p7

So, does that mean the term was in use before it was applied to baseball? Actually, no. There are baseball uses from as much as a year before the 1890 article cited by OED. What’s more, they are all connected to a prominent Oakland ballplayer who almost certainly would have been familiar to reporters at the Oakland Tribune, where the bridgetender story appeared.

Norris “Tip” O’Neill

Norris O’Neill, born in Pennsylvania in 1867, played minor league baseball with teams in various leagues from 1885 to 1896. (He later served as the longtime president of the Western League.) In 1889, he joined the Oakland Colonels of the California League where he was named team captain.

(Norris O’Neill was nicknamed “Tip,” after the much better known major leaguer James “Tip” O’Neill. That original “Tip” was also the inspiration for at least two other baseball players called Tip in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The nickname continued to be applied in later years to other O’Neills, including a Boston newspaper reporter, a jockey, a notorious safe cracker, and, most famously, Thomas P. O’Neill of Massachusetts, longtime Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. There was even a character named Tip O’Neill, a private detective, in a 1936 movie.)

This sketch of Norris “Tip” O’Neill appeared on page 8 of the San Francisco Chronicle on May 23, 1893

The California O’Neill, according to his biography on the website of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), “had a contentious personality and numerous run-ins with the media, fans, opponents, and even his own teammates.” (In 1893, he was named captain of the Stockton, California, team, but the players went on strike, refusing to play for him.) He also fought with umpires, including at least one physical fight that led to charges being brought against O’Neill.

He was known for his banter and back talk, riling opponents, umpires, and the crowd. A letter to the Oakland Tribune said “Tip plays ball with his mouth.”[1]“Robinson Arraigned: A Correspondent Defends Twirler Roscoe Coughlan.” Oakland Tribune, August 21, 1889, p3 San Francisco’s Daily Alta called him “Oakland’s leather-lunged captain.” The Los Angeles Times called him “that ‘noisy man from Oakland,'”[2]“Base-Ball: Oakland’s New Blood Begins to Tell.” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1890, p3 and, in a later article, wrote that “‘Tip’ is a mighty power in the jawbone and can ‘hoodoo’ the opposite side to perfection.”[3]“Hit the Ball Hard.” “Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1893, p5

O’Neill was known for a number of colorful phrases. (The San Francisco Call derided them as “milldewed [sic] expressions that became tiresome years ago.”[4]“League Liners: Items of Interest Concerning California League Players.” San Francisco Call, May 12, 1890, p12 ) Among his expressions, according to an article in the Sacramento Bee , were “aerial hit,” “high roller,” and “herky-jerky.”[5]“Couldn’t Make a Run: The Colonels Hoist the Pennant and Shut Out the Senators.” San Francisco Examiner, April 4, 1890, p3

First Uses and Changing Baseball Meaning

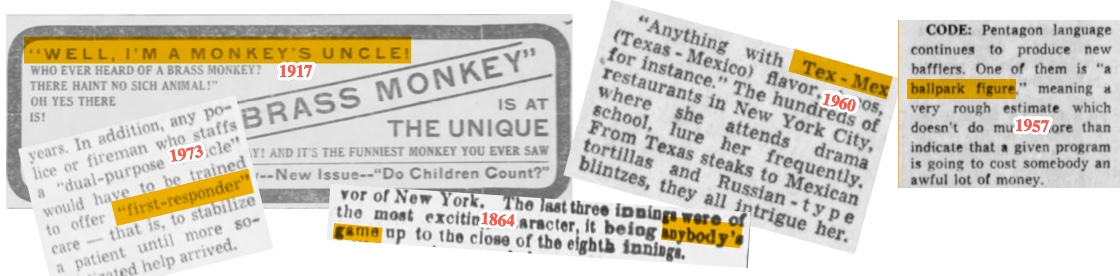

The earliest known use of the term in print was in the San Francisco Chronicle, on May 20, 1889. Here’s how the paper described a sly move pulled off by O’Neill, playing shortstop for Oakland, against the Stockton team:

O’Neill was as full of tricks as a trained elephant. Twice in one inning did ‘Tip’ work that time-worn dodge of holding the ball under his arm, and then when the base-runner led off catch him by a ‘herky-jerky’ throw to the baseman.

“Baker Was Hit Hard: Oakland Gives Stockton a Push Down the Ladder,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 20, 1889, p5

There were other articles using herky-jerky to describe O’Neill’s play in the field, but these referred not to tricky throws but to his frequent errors as he made a less-than-smooth transition from catcher to infielder. Then, in 1891, an article in the Bee described an Oakland pitcher named Gus Tillman whose “performance was worth more than the price of admission.”

He has the funniest herky-jerky movements ever seen, and the spectators roared with laughter. The youngster has considerable speed, however, and when he gets control of the ball and rid of some of his mannerisms, he will doubtless be an efficient hurler.

“Closing on the Dukes,” Sacramento Bee, September 21, 1891, p4

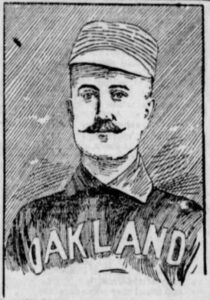

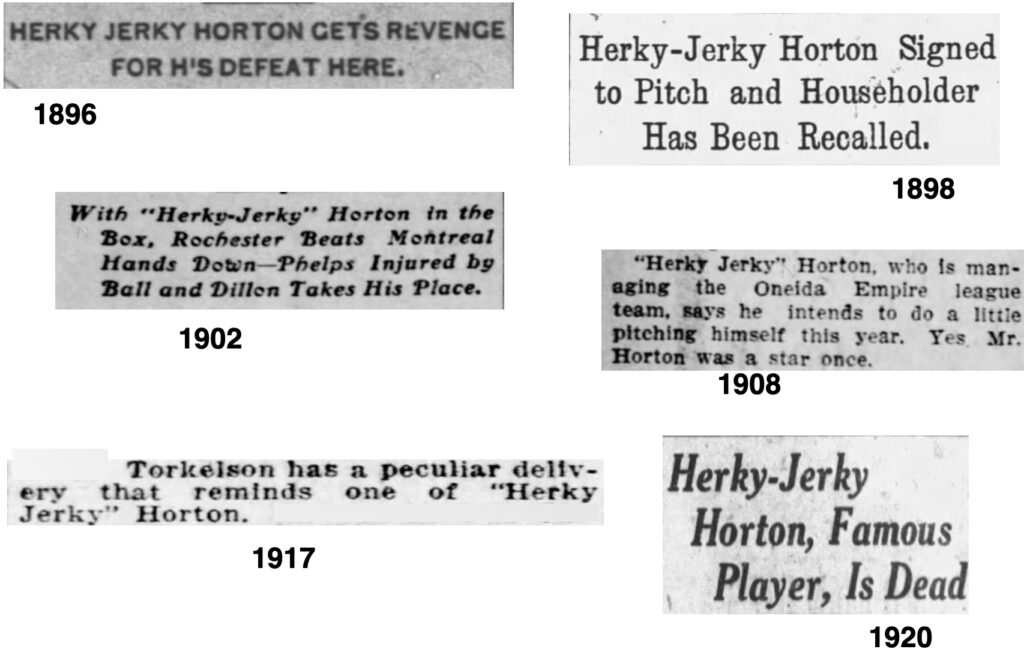

The term really took off beginning in 1895 with Elmer Horton, a pitcher for the Terre Haute (Indiana) Hottentots in the Western Interstate League until the collapse of that league in May and then for the Rockford (Illinois) Reds in the Western Association. In April, the Indianapolis Journal described Horton’s “peculiar manner of delivery”:

He winds himself up like a spring and then by two or three jerks uncoils, and lets the ball fly.

“The Tail Hold Fellows: They Come to Town and Play Ball with Real Players,” Indianapolis Journal, April 12, 1895, p3

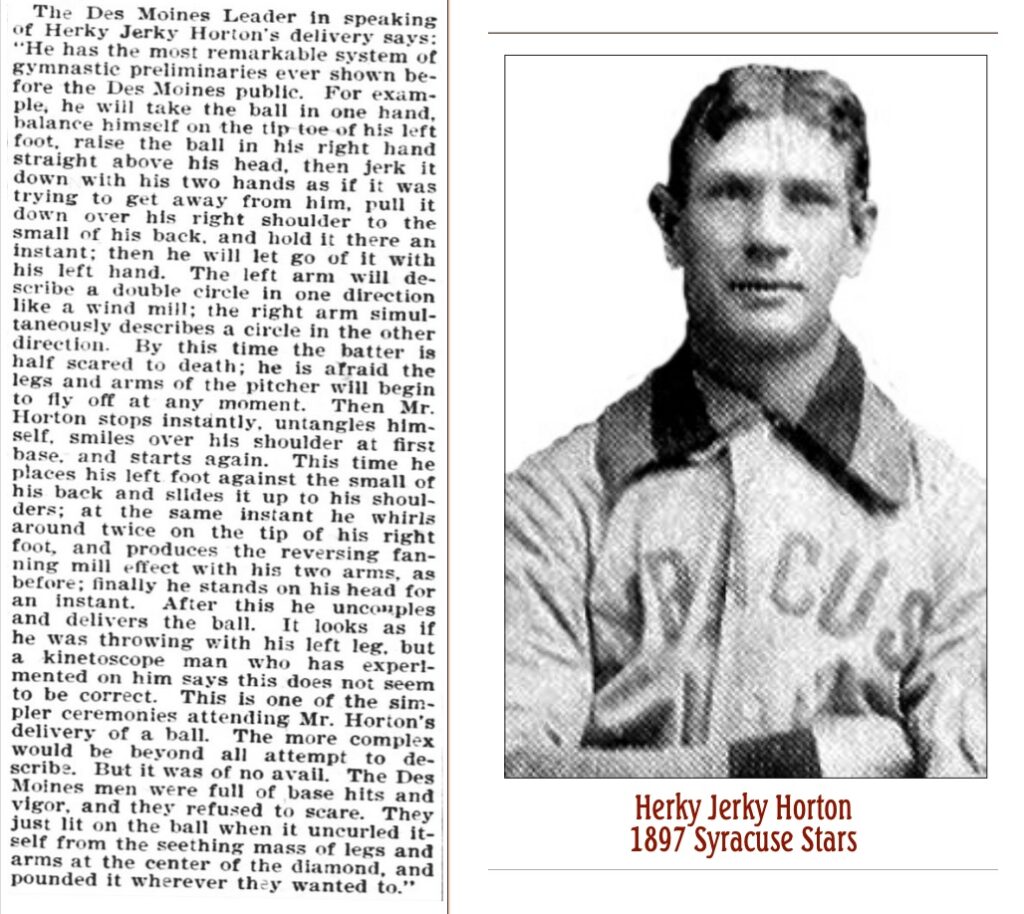

Three months later, the Lincoln (Nebraska) News, reporting on a game between the Lincoln and Rockford teams, offered an even more descriptive account of the pitcher they called H.J. Horton. “The initials H.J. in front of Horton’s label,” they said, “mean Herky Jerky.”

Mr. Horton pitches like a drunken man with an attack of tremens. He grabs a ball, holds it out in front of him, waves his arms frantically in the air like an ancient female stopping a motorcar, winds himself up again, looks at the left foul flag, then at the first baseman, and while the timid men in the crowd are seeking for safety under the seats, he disgorges the ball with a lightning jerk.”

“They Break Even,’ Lincoln (NE) News, July 8, 1895, p5

If that’s not enough of a description for you, check out this even more elaborate one from the Des Moines Leader, along with a photo of Horton, courtesy of the Diamonds in the Dusk profile of him.

Was Horton’s nickname arrived at independently of the earlier use of the term? Perhaps not. From December 1894 to March 1895, before joining Terre Haute, Horton pitched for an amateur team called El Graficos.[6]“Baseball Tomorrow: A Benefit Game to Be Played for Center Fielder Eager.” “Los Angeles Herald, March 30, 1895, p? That was in Los Angeles where the papers, at least, were certainly aware of Tip O’Neill. We may never know, but from 1895 on, including during brief National League appearances with the Pirates and Dodgers, Horton — his fame perhaps enhanced by a catchy nickname — was forever known as Herky Jerky Horton.

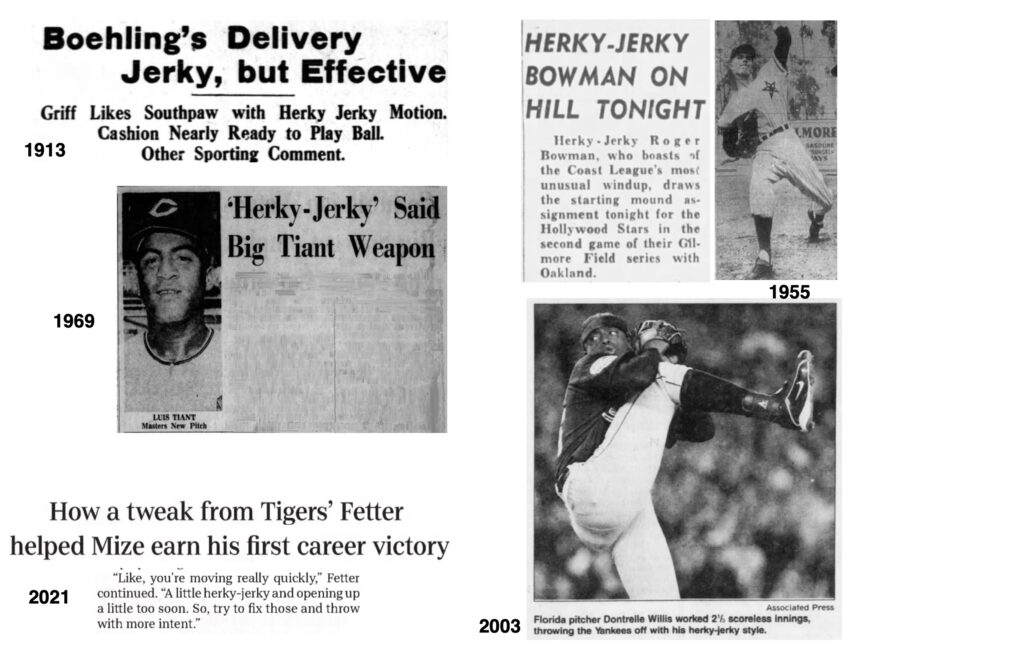

Since Horton’s time, herky-herky — as an adjective, though not as a nickname — has been applied with the same meaning to many other pitchers, though not always as something to be corrected; when combined with good control, speed, and other attributes it can make it hard for batters to time the pitch.

It continues to be used that way, even as non-baseball uses — including pandemic-related ones — have overtaken the sense that began with California’s Tip O’Neill more than 120 years ago.

NOTES

| ↑1 | “Robinson Arraigned: A Correspondent Defends Twirler Roscoe Coughlan.” Oakland Tribune, August 21, 1889, p3 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Base-Ball: Oakland’s New Blood Begins to Tell.” Los Angeles Times, March 13, 1890, p3 |

| ↑3 | “Hit the Ball Hard.” “Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1893, p5 |

| ↑4 | “League Liners: Items of Interest Concerning California League Players.” San Francisco Call, May 12, 1890, p12 |

| ↑5 | “Couldn’t Make a Run: The Colonels Hoist the Pennant and Shut Out the Senators.” San Francisco Examiner, April 4, 1890, p3 |

| ↑6 | “Baseball Tomorrow: A Benefit Game to Be Played for Center Fielder Eager.” “Los Angeles Herald, March 30, 1895, p? |