No matter what your politics, chances are you’ve heard or seen “Clown Prince” applied derisively to some political figure and, perhaps, nodded your head in agreement. It’s been applied, for example, to both Joe Biden and Donald Trump — and to pretty much every president since Richard Nixon.

It’s been used as well to describe vice-presidents aspiring to become or perceived by others as possible presidential successors, including Hubert Humphrey, Spiro Agnew, Dan Quayle, and Mike Pence. Hillary Clinton, well ahead of the 2016 race, was called a “clown princess.”

It’s also been used for non-office-seeking offspring and other relatives of presidents, including Jimmy Carter’s brother Billy, Joe Biden’s son Hunter, and Donald Trump’s son Eric and son-in-law Jared Kushner.

The term has also been used as a form of praise, rather than derision, for princes of comedy from a variety of realms, including stand-up, movies, music. and sports. And even if you’ve not heard or seen any of these, you’ve probably seen Batman’s long-time nemesis the Joker referred to as “the Clown Prince of Crime”.

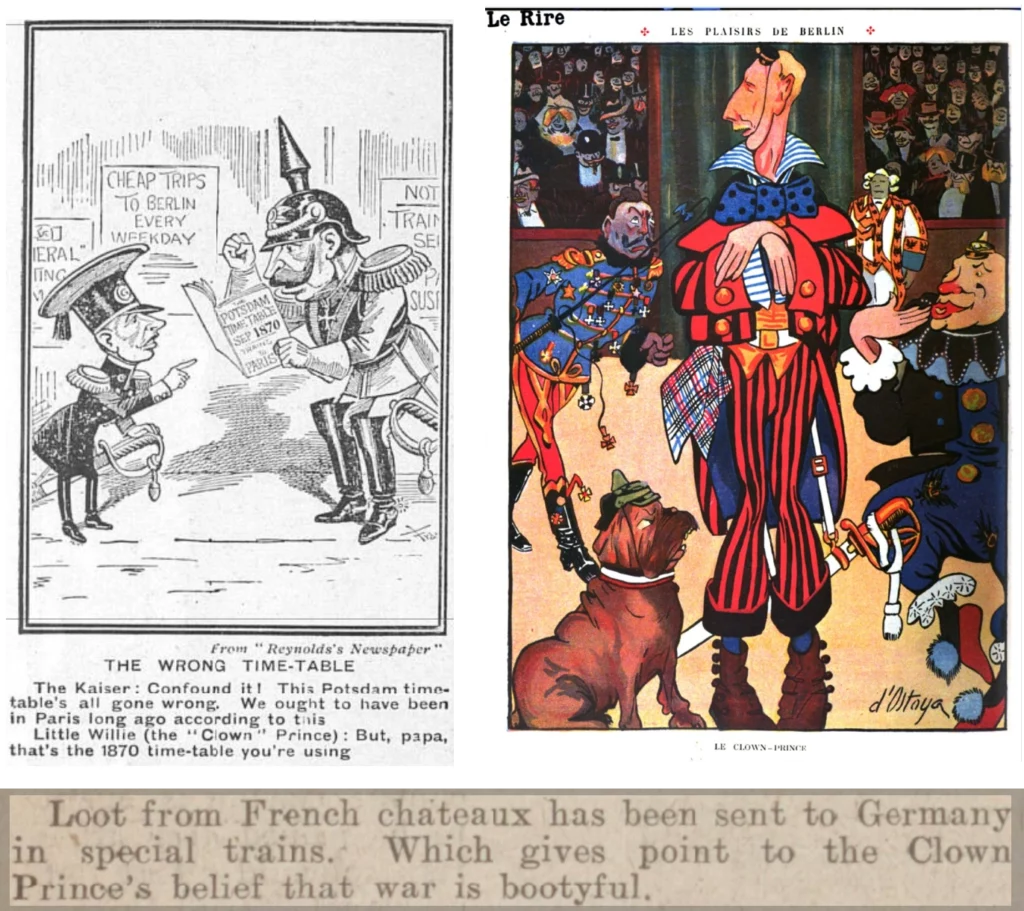

But did you know that the rather obvious pun on the title “Crown Prince” first gained widespread use due to an actual Crown Prince more than 100 years ago?

Prince Wilhelm (1882-1951) had become Crown Prince and heir to the throne of Germany in 1888, at the age of 6, when his father assumed the throne as Kaiser Wilhelm II. When war broke out in 1914, Wilhelm, who, at age 32, had a military career but little major command experience, was put at the head of Germany’s Fifth Army on the Western Front.

The young prince, who had something of a reputation as a playboy and bon vivant, quickly came under ridicule in the British and French press, with cartoons and articles labeling him the “Clown Prince” and “Little Willie.”

The ridicule only increased after the failure of the German Verdun offensive, nominally under Wilhelm’s command, in 1916.

At the end of the war, Wilhelm joined his father in exile in the Netherlands as Germany abolished the monarchy and established the Weimer Republic. He returned to Germany in 1923, toyed with running for president, and become an enthusiastic supporter of Adolf Hitler during the Nazi rise to power, apparently in the hope of seeing a restoration of the monarchy.

With his father’s death in 1941, Wilhelm became the titular head of the inert Holenzollern dynasty. Briefly imprisoned by the Allies at the end of the war, the “Clown Prince” lived out his days in Germany, dying in 1951 at the age of 69.

Clown Princes of Baseball

Interest in “Clown Prince” Wilhelm in the British press faded quickly a couple of years after the end of World War I. It seems to have been kept alive, however, across the Atlantic in the U.S., a reflection, perhaps, of an ongoing interest in European royalty that still exists in this title-less country today. That might explain the flowering of the term in an unexpected place: the great American pastime of baseball.

There were three different baseball personalities who were known as “the Clown Prince of Baseball”: Nick Altrock; Al Schact; and Max Patkin.

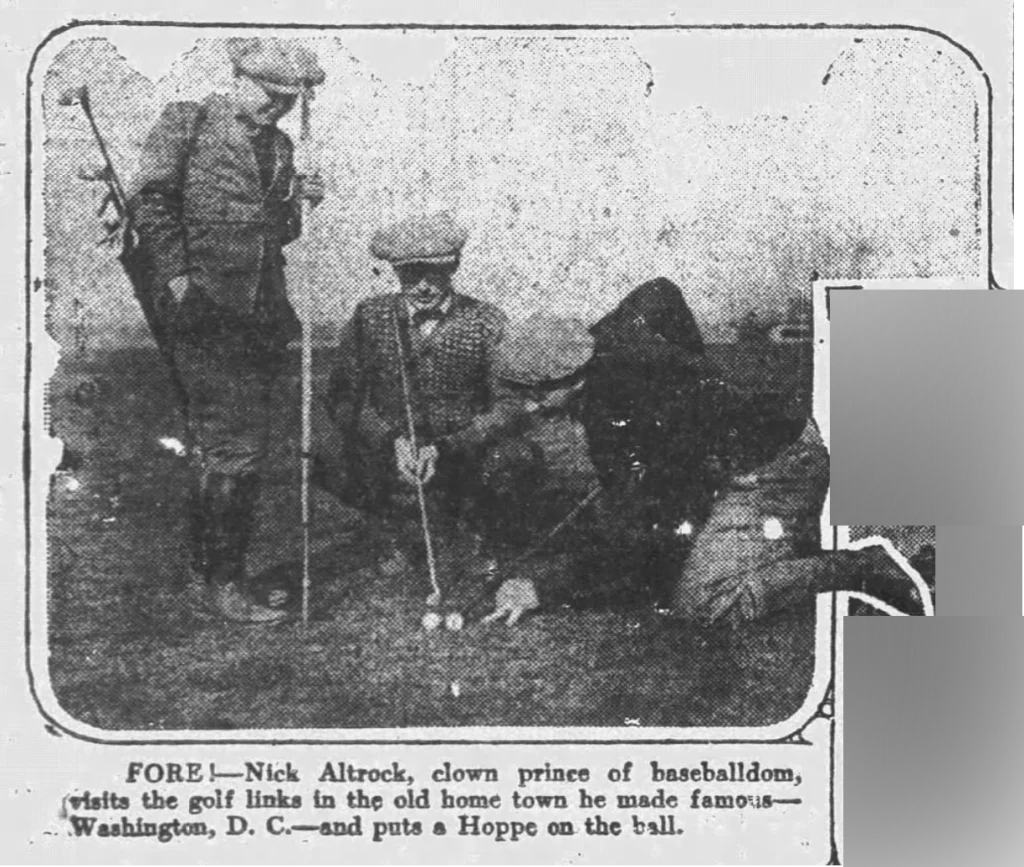

Nick Altrock (1876-1965) was a successful pitcher with several teams, mostly notably with the Chicago White Sox, who he helped win the World Series in 1906. He joined the Washington Senators in 1909, became a coach with the team three years later, and made occasional pitching and later pinch hitting appearances with the Senators. (His last at bat was in 1933, when he was 57.)

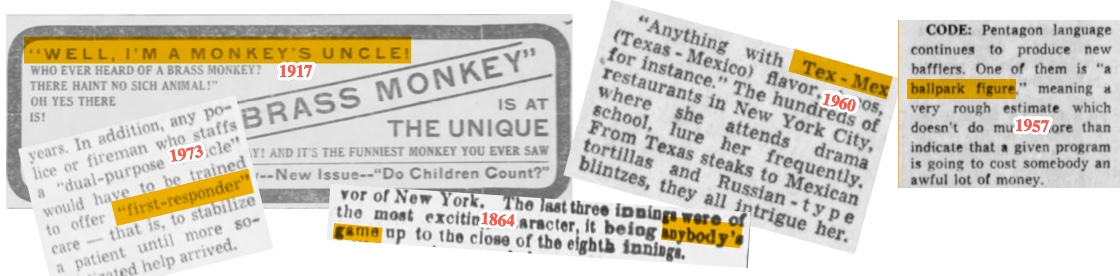

Altrock teamed in on-field comedy antics with another early baseball clown, Germany Schaefer, who was with him in Washington from 1909 to 1914. On November 12, 1918, syndicated columnist Joe Williams suggested that if Altrock, then more a coach than a player, was not available for 1919 “maybe Clark Griffith [owner of the Senators] will sign the clown prince as his jester.” (This was one day after the armistice ending the World War was signed.)

The first known use of the term “Clown Prince of Baseball” — actually “clown prince of baseballdom” — was in an off-season caption on a photo of Altrock in the Camden Post-Telegram in New Jersey in December 1923.

A year later, Al Schact (1892-1984), who had played with the Senators from 1919 to 1921, rejoined the team as a coach and paired with Altrock as the most noted of baseball clowns. (It would be 1930 before newspaper accounts referred to Schact, together with Altrock, as “the clown princes of baseball.”)

In a 1977 interview, Schact told Larry Amman that the term “Clown Prince of Baseball” had been coined about him, by Buffalo sports reporter Jack Yellen, in 1914 after an International League game. Amman included the tale in a 1982 article in Baseball Research Journal, and many sources list Schact as the first to bear the nickname. The facts of the story related by Schact, including a fantastic tale about him coming to the mound in a horse and buggy and pitching in a tuxedo, don’t hold up to scrutiny, and I suspect his claim was a matter of many decades of memories and embellishment.

Max Patkin (1920-1999), who pitched in the minor leagues before entering the Navy in World War II, started as a baseball clown after the war and earned the “Clown Prince” sobriquet previously carried by Altrock and Schact.

Funny Men and Women & the Clown Prince of Crime

Even before World War I, “Clown Prince” was used describe comedic entertainers. Pennsylvania circus owner Dan Rice was called “the clown prince of America” by the Harrisburg Telegraph when he ran for Congress in 1866. (It was not meant as a compliment.)

Tom Evans, a music hall entertainer, appeared on U.K. stages as the Clown Prince for at least two decades at the end of the 19th century.

“Clown Prince” and “Clown Princess” for women have been applied to a long list of comedians, actors, musicians, and others in more modern times, including:

- Danny Kaye

- Red Skelton

- Imogene Coca

- Lucille Ball

- Martha Raye

- Victor Borge

- Carol Burnett

- Eddie Murphy

- Willard Scott

- Biz Markle

- the Harlem Globetrotters

- and many more, including less well-known figures such as:

- Joe Weatherly, “the Clown Prince of NASCAR”;

- Laszlo Bellak, “the Clown Prince of Table Tennis”; and

- Walter Solek, “the Clown Prince of Polka”.

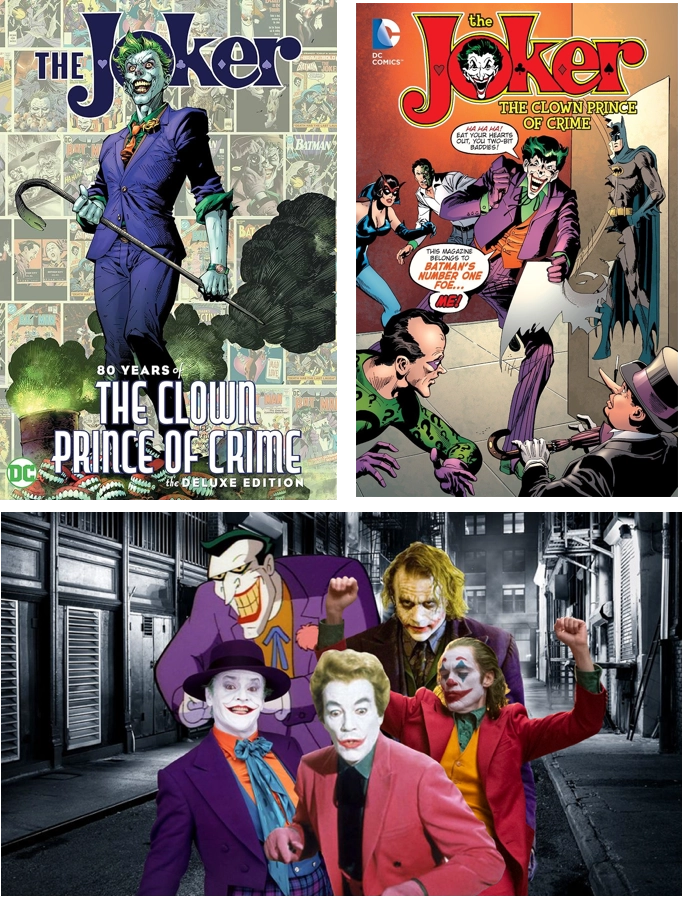

And finally we come to Batman’s arch-enemy, the Clown Prince of Crime, a/k/a/ “The Joker”.

Do a Google Image search for “clown prince” and you’ll have to scroll through several screens worth of images before you find one that’s not about Batman’s famous foe. But although Batman comics made their debut in May 1939 and the Joker was introduced in April 1940, the now ubiquitous moniker “Clown Prince of Crime” is a much later addition.

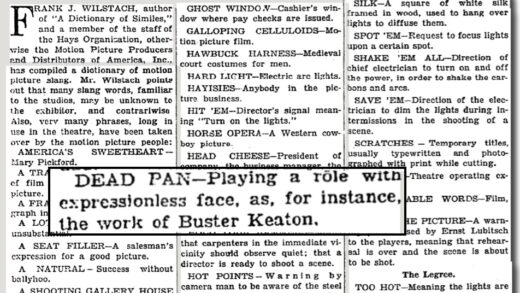

It came, not from the comics, but from the campy 1960s TV show. In the fourth episode of the series, titled “The Joker Is Wild,” first aired on January 26, 1966, Caesar Romero as the Joker announces himself as “I, the Clown Prince of Crime.” (You can watch it, a little past the two-minute mark, in this online of collection of outtakes.)

One More Clown Prince of Crime

Fifteen years before the premier of the Batman TV series, newspaper headlines and stories reported on the murder and lavish funeral of a real criminal know as “the clown prince of crime.” On October 4th, Willie Moretti, an underboss of the Genovese crime family, was gunned down in a New Jersey restaurant. (It’s not clear why he was called by that nickname.)

Moretti had show business, as well as underworld connections. He became Frank Sinatra’s godfather when Sinatra was a young man. Moretti was also a friend of two other entertainers, both of whom performed at his daughter’s wedding.

Those two were also among the many sometimes called “clown princes”: Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis.