In the early days of professional baseball, Chicagoed meant getting shut out — for a whole game or for just an inning or series of innings. It was first used that way in 1870 following a particular game at Dexter Park, a South Side horse racing track with a baseball diamond and stands set up in the oval around which the horses ran.

But the term had roots even earlier in the city’s history. First used 10 years before it was applied to baseball, Chicagoed had ties to the indigenous origins of Chicago’s name and to Abraham Lincoln and his nomination for president at the Republican convention in 1860.

The White Stockings in the East and the West

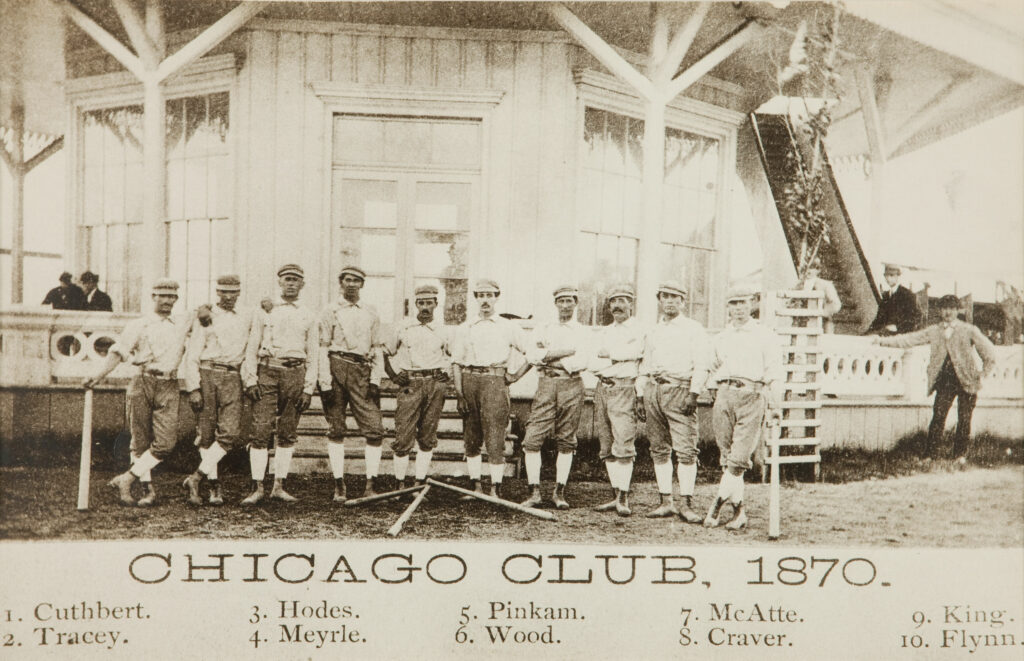

The game that gave birth to the term in baseball, as noted by several writers over the years, took place on July 23, 1870. The Chicago White Stockings, one of the first professional teams, had beat up on lesser clubs in what was then considered “the West.” The White Stockings, a high-priced group of players hired with funds raised by selling shares in the team, then traveled east in early July to take on teams in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and other cities.

The confident — maybe overconfident — White Stockings suffered three losses in their two-week swing through the East: to the Atlantics and the Mutuals in Brooklyn (then still its own city); and the Athletics in Philadelphia. Those unexpected losses brought derision from scribes in New York and other states.

- “…they have to learn a great deal yet before they can expect to cope successfully with such organizations as the Atlantics, Mutuals, Athletics…” – Brooklyn Times

- “This is the worst defeat of the season, and should convince the White Stockings that it takes something more than talk to become the champion base ball club of the country, such as they had proclaimed themselves.” — Daily Chronicle (Nebraska City, Nebraska)

- “It will take considerable Chicago yarn to darn the hole worn in their new ‘white stockings’ recently. It is said somewhere from twenty to thirty skeins will be required.” —Stark County Democrat (Canton, Ohio).

- “If the bombastic Chicagoites are capable of feeling humiliation and disgrace, they will lose no time in going home, there to be forgotten in the stench of the Chicago river….” — Sioux City Journal

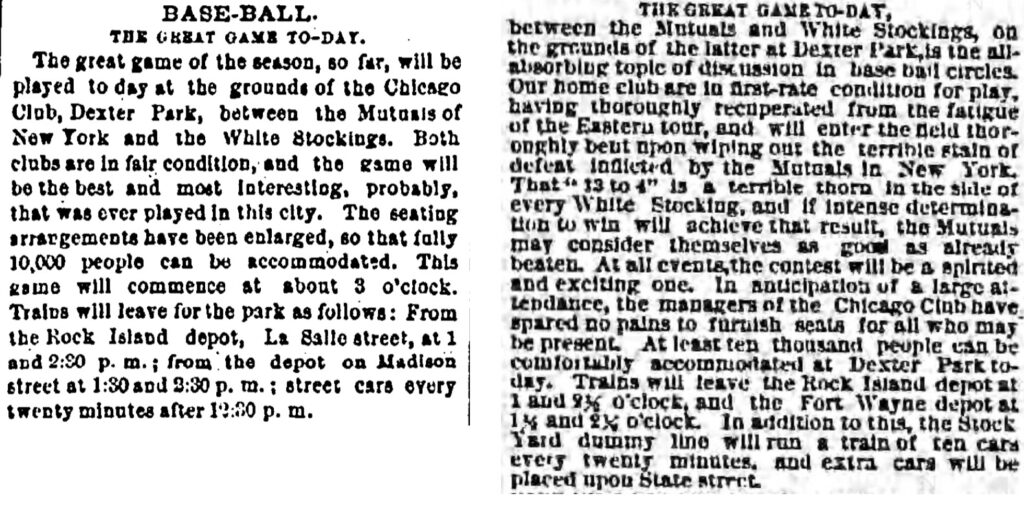

There was some wringing of hands and gnashing of teeth in Chicago, to be sure, but with a visit from the Mutuals scheduled for Dexter Park on the 23rd, there was also confidence that the results would be different on the White Stockings’ home turf.

“By this time,” [said the Chicago Tribune a week before the game] “it is expected that our professional club will be in good condition physically, and in every way prepared to do their best to redeem the humiliating defeat which they suffered at the hand of the Mutuals when in New York.”

On the day of the game, the Chicago Republican anticipated it would be “the best and most interesting, probably, that ever was played in this city.” The White Stockings, reported the Chicago Tribune, “having thoroughly recuperated from the fatigue of the Eastern tour” are confident of victory and added that if their confidence was any indication “the Mutuals may consider themselves as good as already beaten.”

But it was not to be.

Chicago Chicagoed

The Mutuals, after a warmup game against a non-professional Chicago team (the Amateurs) on July 22nd, came to Dexter Park the next day for the rematch against the White Stockings.

The New Yorkers won again, by the same margin — nine runs — by which they’d defeated the Chicagoans in the East. But if the 13-4 loss in Brooklyn was “humiliating” to the Chicagoans, the 9-0 shutout — a rarity in those early days — on the White Stockings’ home ground was practically apocalyptic.

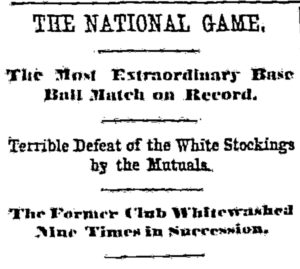

The Chicago Tribune headline on the 24th called the game “The Most Extraordinary Base Ball Match on Record” and a “Terrible Defeat of the White Stockings by the Mutuals.”

“Who would have thought it?” [said the paper] “What sane individual, conversant with the general subject, would have incurred the risk of an examination before a commission of lunacy, by admitting the mere possibility, much less by uttering the prediction? Yet it was so.”

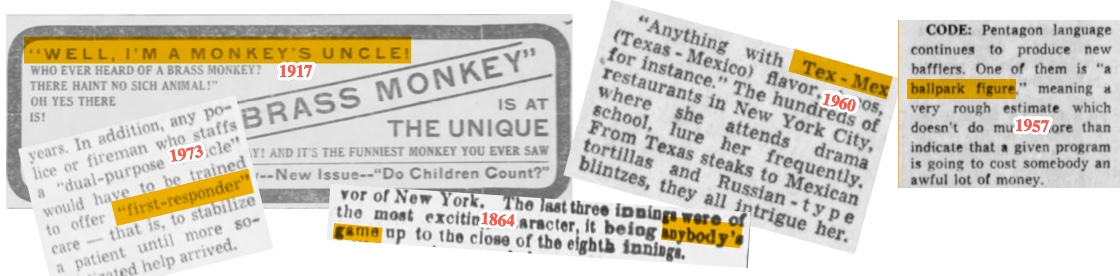

It was four days after the game, on July 27th, that the term Chicagoed was first used to describe a baseball team being shut out. It was in an article in the New York Herald about a game in Brooklyn where a team of Brooklyn players (“The Selected”) was held scoreless for five innings before finally losing to the Atlantics, 29-9.

“Of the game itself very little need be said,” reported the Herald. But, it added

The Skunk in Chicago

It’s unknown if the writer for the Herald knew it, but the word he wanted to replace — skunked — and the word he wanted to replace it with — Chicagoed — are related. The city, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, derives its name from a word

“in the language spoken by the Miami and Illinois peoples meaning “striped skunk, ” a word they also applied to the wild leek … This became the Indian name for the Chicago River, in recognition of the presence of wild leeks in the watershed. When early French explorers began adopting the word, with a variety of spellings, in the late seventeenth century, it came to refer to the site at the mouth of the Chicago River.”

Skunked had been used to mean “shut out” in baseball since at least 1859 , when the Brooklyn Times, describing a 22-12 win of the Atlantics over the Eckfords, noted that, despite winning, “In several innings the Atlantics were ‘skunked’ beautifully.” (The box score of the game showed no runs scored by the winners in four of the last five innings.)

It’s unclear how skunked came to mean “shut out” (or the related “To defeat, beat, or get the better of (another person, team, etc.)” (Oxford English Dictionary). But it’s earliest use in the sense of a shutout came in 1839, 31 years before that 1870 article.

It came not in baseball or any sport or game, but in presidential politics.

On December 24, 1839, the Detroit Free Press, published a brief item in response to a letter in the Baltimore Post predicting how many electoral college votes the Whig William Henry Harrison might win in an 1840 race against incumbent President Martin Van Buren.

The Free Press proved to be not much a prognosticator, even of their home state; Harrison ended up winning 19 states, including (narrowly) Michigan, to Van Buren’s seven. But their use of skunked to mean failing to score anything at all lived on. (The same could not be said of Harrison, who died on April 4, 1841, exactly one month after being sworn in as president.)

The term skunked to mean shut out, if not the actual result, was applied in press accounts to losers in the next four presidential elections: Henry Clay (1844); Lewis Cass (1848); Winfield Scott (1852); and former president Millard Fillmore (attempting a comeback in 1856). It was used, as well, to describe the efforts of numerous seekers of lesser offices around the country.

But it would take the nomination of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 to bring Chicagoed together with its etymological cousin skunked.

The Chicago Convention of 1860

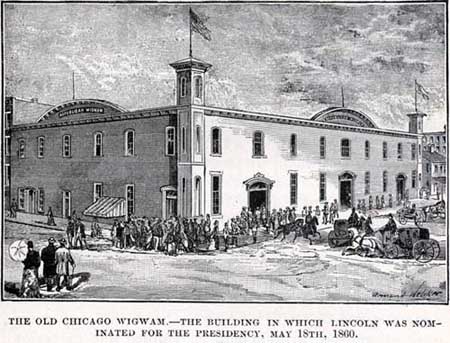

Lincoln was hardly a sure thing heading into the Republican convention, held in a temporary wooden facility dubbed the “Wigwam” from May 16th to May 18th, with voting taking place on the third day. U.S. Senator William Seward of New York was considered the favorite and led Lincoln 173-1/2 to 102 after the first ballot, with another 189-1/2 votes spread among several others.

The gap closed almost entirely on the second ballot, with the shift of nearly the entire Pennsylvania delegation from favorite son Senator Simon Cameron to Lincoln making up most of the difference. Lincoln moved ahead on the third ballot, but remained just short of a majority before members of several delegations switched their votes from other candidates to give him the nomination.

The three earliest known uses in print of Chicagoed as a transitive verb appeared in Ohio newspapers in the week after the close of the Chicago convention. None of these three specifically referenced an electoral shutout or possible shutout. But all were tied to the convention and to an overwhelming victory or loss.

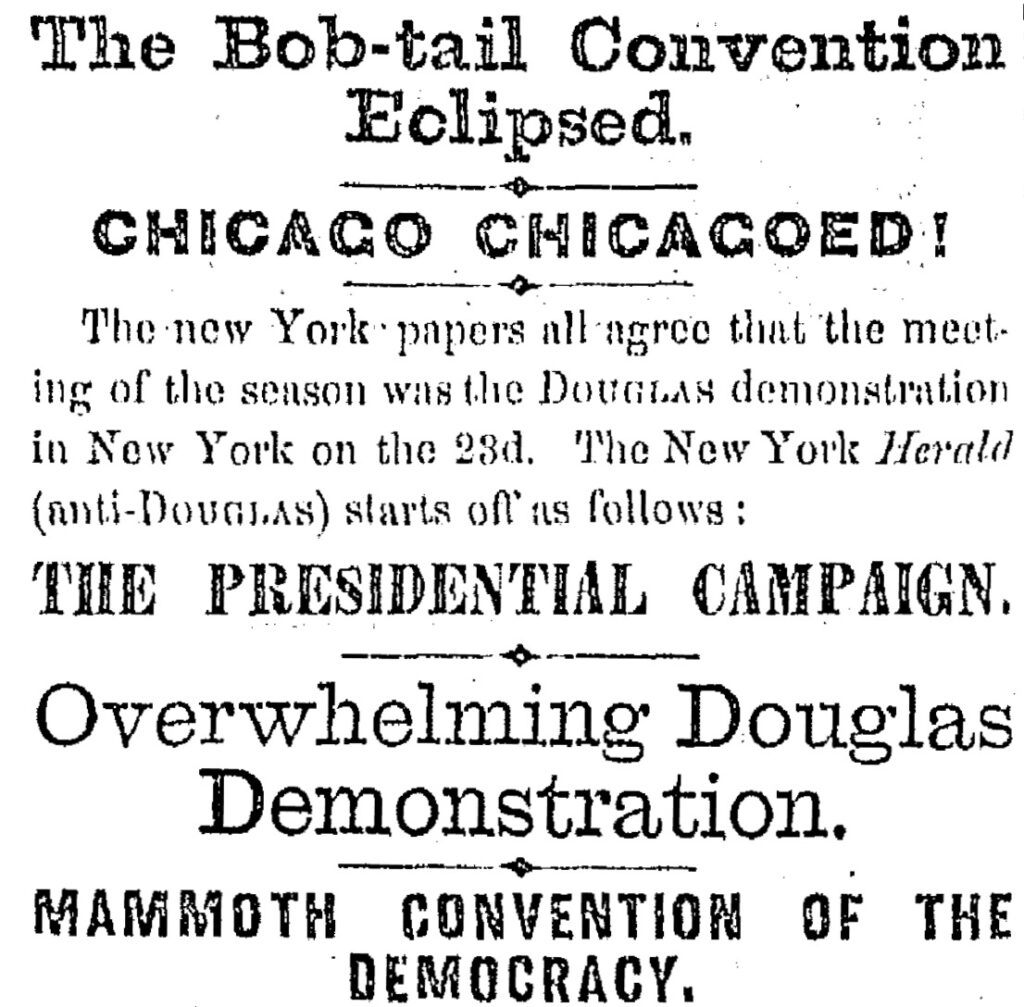

- On May 24th, the Cleveland Plain Dealer reprinted a New York Herald article about a large Democratic rally in support of Stephen A. Douglas at New York’s Cooper Union and the streets around it. The rally was said to surpass both the Democracts’ convention in Charleston — known as the Bob-Tail Convention because it was cut short when Douglas secured the most votes but not the required two-thirds majority — and the Republican convention in Chicago. The Plain Dealer added its own introduction and a headline: “The Bob-Tail Convention Eclipsed. Chicago Chicagoed!”

- The same day, the Holmes County Farmer in Millersburg, Ohio, ran a brief item with the headline “Chicagoed” about a Millersburg delegate to the Republican convention named R.K. Enos who, it said, was “Chicagoed,” or cleaned out of all his money, at a card game. Not mentioned in the article was something more consequential: Enos was one of four Ohio delegates whose switch of their votes from Ohio Governor Salmon Chase to Lincoln on the third ballot had put the latter over the top (and led others to do the same).

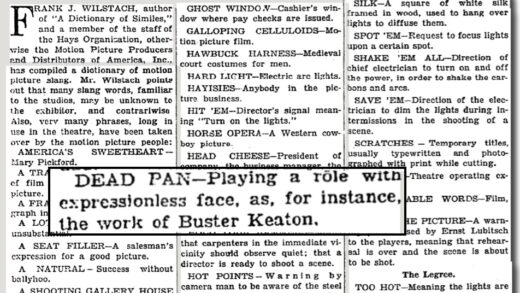

- Finally, on the 25th, a two-paragraph story in the Plain Dealer offered what seemed to be a fervent wish that the newly nominated Lincoln would be “Chicagoed” in November. If the meaning was unclear, this line made it less so: “We prefer the Indian to the English word”. In other words, Chicagoed instead of skunked. Or as a later (1889) article put it, “The substitution of ‘Chicagoed’ for ‘skunked’ still prevails chiefly in society where the older term is deemed malodorous and its Indian substitute more polite.”

Chicagoed was used again, sometimes with slightly different meanings, in writings about Lincoln’s re-election in 1864. One article, with the headline “Chicagoed,” implied that the delegates four years earlier had awarded him the nomination unfairly – “with only one-third of their votes.” (In fact, Lincoln’s share on the final multi-candidate ballot, before switches took place, was 37.5%, but only if the numbers of the southern and border states who declined to send electors to the convention were counted.)

In 1868, another Ohio paper, the Times-Democrat in Lima, described Ulysses S. Grant’s unanimous nomination at that year’s Republican convention as having been “Chicagoed” “in a little game of politics,” and predicted he would be “Chicagoed” in November. The term continued to be used about local elections as late as the 1880s.

It was also used as shorthand for other events and activities of a type associated in the public mind with Chicago, including fires (after the Chicago Fire of 1871), organized crime, and political corruption. But the baseball meaning was the predominant one until fading away in the 1910s, presumably because changing rules made shutouts less of a rarity.

“Chicagoed” Down Under

The terms Chicago and Chicagoed, for shutout games, did live on in baseball beyond the 1910s (and beyond the earlier political use). But it was in a surprising location, far from the birthplace of the term and the game: in Australia. And it was a later incarnation of the Chicago White Stockings that helped bring it there.

It’s uncertain when baseball was first played in Australia; some sources date it as early as the 1850s when it was played by visiting or expatriate Americans, but it was certainly being played by the mid-1880s.

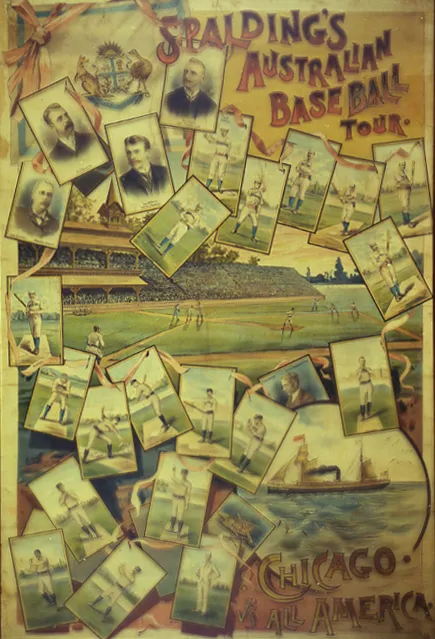

The real spur, though, came with the visit of the Albert Spalding-led White Stockings and an opposing team of “All-Americas” who played a dozen games in different Australian cities between December 10, 1888 and January 5, 1889. (After leaving Australia, the teams brought the game to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Egypt, Italy, France, and the United Kingdom before returning to the U.S. in April 1889.)

On October 4, 1889, the South Australia Register in Adelaide carried a “Baseball Notes” article explaining the rules and other facts about the game. Included were these lines:

“When a team fails to score in a match it is called a ‘Chicago’ game, and in America they are said to be ‘shut out’ or ‘whitewashed.’ The Goodwoods were the first South Australian club to win a ‘Chicago’ game, the score being 7 to 0.”

The term continued to be used in accounts of Australian baseball games over many years, until at least 1937, when the Maitland Daily Mercury in New South Wales previewed an upcoming game this way:

“Hamilton, whom Maitland ‘Chicagoed’ last week, played a draw with West the week previously, and should this be an indication, Maitland should win.”

Since then, the term Chicagoed, born in 1860 to describe a shutout or decisive loss in politics and later used in baseball, has pretty much been Chicagoed itself.